Suggestions for Managing Grief in the Time of COVID-19

June 10, 2020 11:26 AM

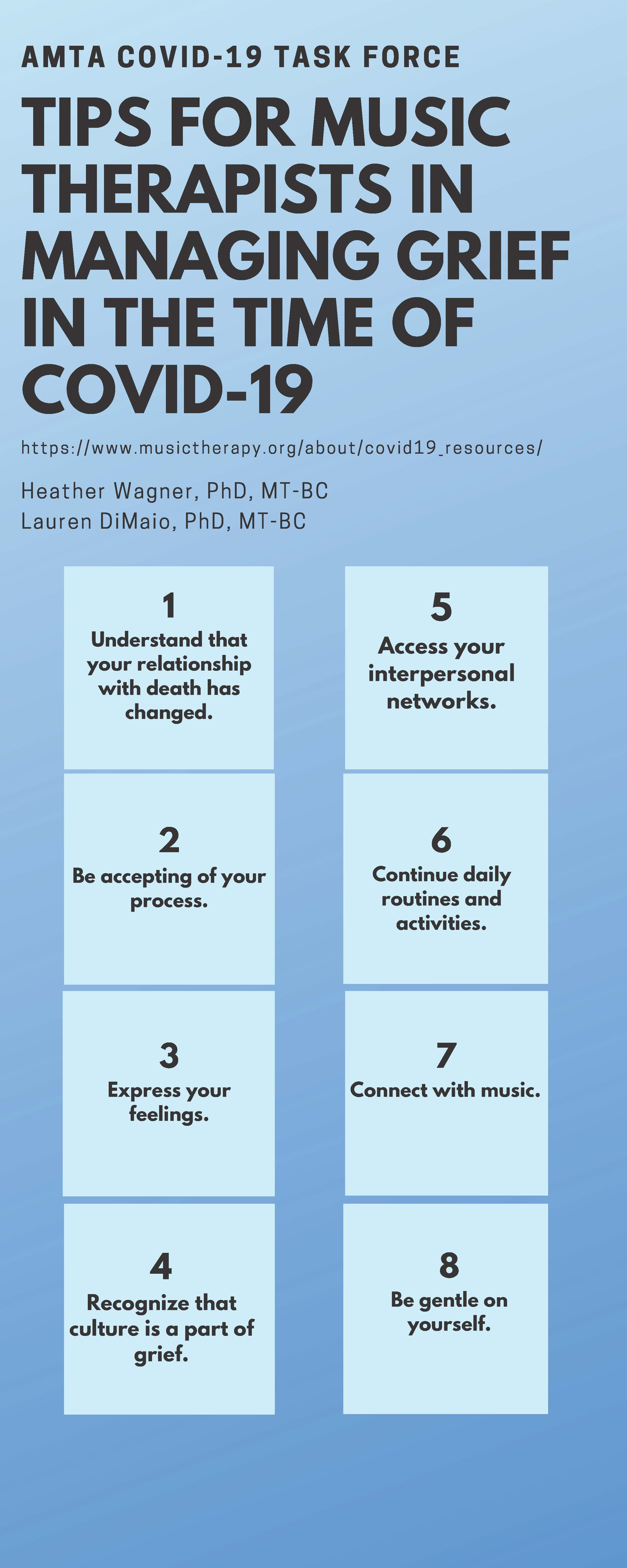

Suggestions for Music Therapists Managing Grief in the Time of COVID-19

AMTA COVID-19 Task Force, prepared by Heather Wagner, PhD, MT-BC; Lauren DiMaio, PhD, MT-BC

As many music therapists transition back to providing services during this COVID-19 experience, AMTA recognizes that the workplace will look and feel differently. One factor in these differences may include grief. Grief may relate to losses associated with normalcy, staff and patient turnover, and restrictions on your clinical practice. Grief may also relate to a death, or even many deaths. Music therapists grieve, both personally and professionally. This document is meant to acknowledge that music therapists are grieving and to offer support.

Grief is a part of the COVID-19 experience (National Response Coordination Center [NRCC] Healthcare Resilience Task Force, 2020; Penn, 2020). Though society does more to help us hide our grief, it is helpful to fully experience it and heal. Because music therapists will be processing this grief while still providing clinical services, a more full understanding of this experience may be beneficial.

Professional grief is complex (Zisook & Shear, 2009). Professional grief is different from personal grief in that the experience of death is related to your job. This unique version of grief encompasses clients, coworkers, and family, friends, and other caregivers related to clients. Professional grief may feel similar to personal grief in that we may experience some of the same responses to death and losses (Dyregrov & Dyregrov, 2008). Unique to professional grief is that society tends to not acknowledge it. Family and friends may not “check in” on us when we are experiencing professional grief.

Also, a professional grief experience unique to COVID-19 is the possibility that you did not get to say goodbye. If a client or coworker died (either from COVID-19 or while you were unable to provide direct services) participating in any form of a relationship completion may not have happened. Additionally, how a person died impacts grief (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Shear, Simon, Wall, Zisook, Neimeyer, Duan, et al., 2011). If the death is viewed as preventable, that perception will impact how you grieve. If the person died in pain or alone, those images may intrude. You may be further impacted by your inability to provide support through music therapy due to quarantine restrictions.

While there is no one way to deal with the grief you may be experiencing, it is hoped that these suggestions will help you find healing and the capacity to continue to provide high quality music therapy services to your clients while taking good care of yourself (Cleveland Clinic, 2020; NRCC Healthcare Resilience Task Force, 2020; Penn, 2020; Worden, 2008).

- Understand that your relationship with death has changed. The grief you are faced with now may activate your own past experiences with death. New deaths may stimulate any unresolved grief and even past deaths that you thought were resolved. It may also cause you to think about your family and yourself dying.

- Be accepting of your process. You may vacillate between feeling states, energy levels, and even feelings of competence. Struggling between the pain of grief and learning how to adapt are two important tasks. There is no time frame for grief.

- Express your feelings. It is important to express your emotional responses. This release can be done verbally, musically, or through another modality.

- Recognize that culture is a part of grief. Look to your beliefs and culture for support. Now is the time to ask: How did my family teach me to grieve and would that be helpful now? If not, try new ways to grieve.

- Access your interpersonal networks. Share your experiences with other people such as coworkers or peer support networks. Connecting with people who understand and can hold space for you, and for whom you may be able to hold space, can help you adjust to these losses. Not all coworkers will be accepting and inclusive, so if someone does not respond in a positive way, keep looking. One person cannot meet all of your grief needs.

- Continue daily routines and activities. Make time to engage in the activities that energize, restore, and fortify you. It is also OK, and encouraged, for you to connect with joy in your daily life and work.

- Connect with music. Is there a way for music to help you grieve? Would singing or playing or listening to a song that was important to that person be a helpful way to honor them? Would taking some time and improvising help release some emotions? Would a musical journal help? Maybe not, or maybe not now.

- Be gentle on yourself. COVID-19 and its effects are like nothing else our current society has experienced. Set boundaries as needed, and even say no to tasks if that is what you need. Be patient as you learn to navigate through this new landscape.

It is possible that you are not grieving but are aware of your coworkers’ grief. Below are helpful hints to support a grieving coworker.

- Ask directly about their grief. Asking “How are you” has become more of a greeting than an actual question. Instead try asking, “How are you doing since (insert name if possible) died?” Grievers miss hearing the name of the person, so using that name lets the griever know that you care and that you are willing to truly listen about their grief.

- Remember special dates. Perhaps your coworker always visited this special deceased client on Wednesdays. Checking in on them on Wednesdays would then be important. You might say, “I know you usually saw (insert name) on Wednesdays. So I am wondering how today is for you.”

- Establish rituals. Sometimes rituals are helpful. Perhaps having a ritual for your work community would be helpful. You can talk to an administrator and volunteer to help design and facilitate such a ritual. Please be careful that this does not turn into a religious ritual, but rather one that honors everyone’s experience.

- Send notes of support. Sometimes taking time to visit face to face with coworkers is not possible. Taking a minute and writing a note is another form of support.

- Be mindful of your language. Avoid language like “I know how you feel,” or advice like “What you should do is…” Also avoid, “They are in a better place,” because this statement makes assumptions about someone's beliefs.

- Check in. Remind yourself to check in a month from now.

The music therapy community will likely need to continually adapt and respond to emerging challenges of COVID-19. AMTA will be here to support our community through this. We encourage you to reach out for help when needed, and we hope you will find meaning even in these difficult times.

References and Resources:

- American Psychiatric Association, (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Bruce, C. (2007). Helping patients, families, caregivers, and physicians, in the grieving process. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 107(supplement 7), ES33-ES40. https://jaoa.org/article.aspx?articleid=2093584

- Cleveland Clinic (2020, April 20). Losing patients to COVID-19 and managing grief. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/losing-patients-to-covid-19-and-managing-grief/

- Dyregrov, K. & Dyregrov, A. (2008). Effective grief and bereavement support: The role of family, friends, colleagues, schools and support professionals. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London

- National Response Coordination Center Healthcare Resilience Task Force. (2020, April 10). Grief following patient deaths during COVID-19. https://files.asprtracie.hhs.gov/documents/grief-following-patient-deaths-during-covid-19.pdf

- Penn, A. (2020, April 3). Making room for grief in COVID-19. https://www.psychcongress.com/article/making-room-grief-during-covid-19?page=0

- Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., N. Duan, N., … Keshaviah, A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117.

- Stroebe, M. & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23, 197-224.

- Worden, J.W. (2008). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (4th ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

- Zisook, S. & Shear, K. (2009). Grief and bereavement: What psychiatrists need to know. World Psychiatry, 8(2), 67-74.

Research and Resources Related to Music Therapy and Grief:

- DiMaio, L. (2015). A content analysis of interviews with music therapists who work with grieving adults in contemporary hospice care. In S. Brooke & M. Miraglia (Eds.). Using creative therapies to cope with grief and loss (pp. 210-235). Charles Thomas Publisher.

- Iliya, A. Y. (2015). Music therapy as grief therapy for adults with mental illness and complicated grief: A pilot study. Death Studies, 39, 173-184.

- Krout, R. (2005). Applications of music therapist-composed songs in creating participant connections and facilitating rituals during one-time bereavement support groups and programs. Music Therapy Perspectives, 23(2), 118-128.

- O’Callaghan, C., McDermott, F., Hudson, P., & Zalcberg, J. (2013). Sound “continuing bonds”: Music’s relevance for bereaved caregivers. Death Studies, 37(2), 101-125.

- Sekeles, C. (2007). Music therapy: Death and grief. Barcelona Publishers.

- Sato, Y. (2020). When a music therapist grieves. Music Therapy Perspectives, 38(1), 17–19.

- Wilkerson, A., DiMaio, L., & Sato, Y. (2017). Countertransference in end-of-life music therapy. Music Therapy Perspectives, 35(1), 13–22.

- https://musictherapyeolcare.com/about/

- Wlodarczyk, N. (2010). The effect of a single-session music therapy group intervention for grief resolution on the disenfranchised grief of hospice workers (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Dissertations & Theses: A&I. (Publication No. AAT 3462370).

Back